LAW CHAMBER OF HINESH RATHOD (ADVOCATE)

1.9K subscribers

About LAW CHAMBER OF HINESH RATHOD (ADVOCATE)

Law chamber Group, a platform dedicated to disseminating daily legal awareness, general knowledge, and court case updates from around the globe. Objective is to promote legal awareness and education, and to keep members informed about the latest developments in the legal landscape. Advocate *Hinesh N. Rathod* is available to provide legal advice, support, and representation to ensure your rights are protected and interests are served. Please feel free to reach out for any legal assistance or queries. Contact Number: +91 8652544618 Email id: [email protected]

Similar Channels

Swipe to see more

Posts

↗️ *SUPREME COURT OF INDIA* CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CIVIL APPEAL NO. 7108 OF 2025 (@SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (C) NO. 4307 OF 2022) SULTHAN SAID IBRAHIM VERSUS PRAKASAN & ORS. May 23rd, 2025 *Supreme Court upholds dismissal of Appeal, orders handover of possession in protracted property dispute* *Decision:* The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal, affirming the lower courts' rulings that the appellant's application for deletion from the party array was barred by res judicata and rejecting his tenancy claim. The Court ordered the appellant to pay costs and directed the Executing Court to ensure the respondent receives possession of the suit property within two months. *Act:* Specific Relief Act, 1963; Kerala Buildings (Lease and Rent Control) Act, 1965; Code of Civil Procedure, 1908.

↗️ *SUPREME COURT OF INDIA* CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CIVIL APPEAL NO. 2526 OF 2025 (ARISING OUT OF SLP (CIVIL) No. 20178 OF 2022) K. UMADEVI VERSUS GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU & ORS. MAY 23, 2025. *Set aside the order of the Division Bench of the Madras High Court which had denied maternity leave to a government teacher for the birth of her third child, citing State policy restricting benefits to two children.* *A bench of Justice Abhay Oka and Justice Ujjal Bhuyan held that maternity benefits are part of reproductive rights and that maternity leave is integral to those benefits.* *“We have delved into the concept of reproductive rights and have held that maternity benefits are a part of reproductive rights and maternity leave is integral to maternity benefits. Therefore, the impugned order has been set aside. The division bench order has been set aside,” the Supreme Court observed.* *"Maternity leave is integral to maternity benefits. Reproductive rights are now recognized as part of several intersecting domains of international human rights law viz. the right to health, right to privacy, right to equality and non-discrimination and the right to dignity."*

📌 *Principle of Stare Decisis* • It means 'to abide by things decided'. • It is legal principle that courts should follow precedents set by previous decisions when making rulings in similar cases. • Article 141 of the Constitution of India - "The law declared by the Supreme Court shall be binding all courts within the territory of India". ◽ *Exception to the Rule of Stare Decisis* *1. Per incuriam* Per incuriam means "wrongly decided". Per incuriam Judgments are those which are wrongly decided due to Wrongful interpretation of law. Ignorance of a relevant statue or Ignorance of binding precedent by the Judges. Such Judgments are not binding on the lower courts. *2. Sub Silentio* It means 'In Silence' and is used to refer to something that is not expressly stated. It refers to a situation in which a court make a ruling or applies a principle without taking into account the applicable law or any arguments. Such Judgments are lose their precedential value and are not binding.

Sec 180 BNSS: Examination of witnesses by police (1) Any police officer making an investigation under this Chapter, or any police officer not below such rank as the State Government may, by general or special order, prescribe in this behalf, acting on the requisition of such officer, may examine orally any person supposed to be acquainted with the facts and circumstances of the case. (2) Such person shall be bound to answer truly all questions relating to such case put to him by such officer, other than questions the answers to which would have a tendency to expose him to a criminal charge or to a penalty or forfeiture. Article 20(3) of the Indian Constitution guarantees the fundamental right against self-incrimination, meaning no person accused of an offense can be compelled to be a witness against themselves. (3) The police officer may reduce into writing any statement made to him in the course of an examination under this section; and if he does so, he shall make a separate and true record of the statement of each such person whose statement he records: Provided that statement made under this sub-section may also be recorded by audio-video electronic means: Provided further that the statement of a woman against whom an offence under section 64, section 65, section 66, section 67, section 68, section 69, section 70, section 71, section 74, section 75, section 76, section 77, section 78, section 79 or section 124 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 is alleged to have been committed or attempted, shall be recorded, by a woman police officer or any woman officer. Sec 181 BNSS: Statements to police and use thereof (1)No statement made by any person to a police officer in the course of an investigation under this Chapter, shall, if reduced to writing, be signed by the person making it; nor shall any such statement or any record thereof, whether in a police diary or otherwise, or any part of such statement or record, be used for any purpose, save as hereinafter provided, at any inquiry or trial in respect of any offence under investigation at the time when such statement was made:

↗️ *SUPREME COURT OF INDIA* LAKSHYA TAWAR Vs CENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION SLP(Crl) No. 5480/2025 Date : 22-05-2025 *Granted bail in a special leave petition specifically on the ground that the Allahabad High Court, which was dealing with the bail application of the present petitioner, adjourned the matter 27 times. The Court observed that in matters of personal liberty, the High Courts are not expected to keep adjourning the matter. Consequently, the Court, while disposing of the matter, stated that the application for bail pending before the High Court is rendered infructuous.* *"In the matters of personal liberty, the High Courts are not expected to keep the matter pending for such a long time and do nothing, except for adjourning from time to time. The petitioner has been incarcerated for a period of more than four years. The complainant's evidence has also been recorded. In that view of the matter, and taking into consideration the peculiar facts and circumstances of the case, we are inclined to grant bail to the petitioner."*

Legal Set-off [Order VIII Rule 6] The defendant may at the first hearing of the suit i.e. the filing of the written statement may present his pleadings claiming the debt against the plaintiff by way of set-off in a suit for recovery of money instituted by the plaintiff, if the following requisites are fulfilled or in other words, we can say what are the things to be taken care of in making a claim or conditions of set-off: 1. It is a suit for recovery of money. For e.g. A sues B for Rs. 12,000. B cannot claim set-off the claim for damages for breach of contract for specific performance. 2. Claim of defendant must be for ascertained sum of money i.e. specific and certain. For e.g. A sues B on a bill of exchange. B alleges that A has wrongfully neglected to ensure B’s goods and is liable to him in compensation which he claims to set-off. The amount not being ascertained cannot be set-off. [Illustration (c) to Rule 6]. On the other hand, where A brings a suit for recovery of Rs. 5000 against B, the latter can claim set-off of Rs. 2000 for damages for house trespass committed by A as the amount is ascertained. 3. Such sum should be legally recoverable, i.e. it should not be time barred. For e.g. A sues B for Rs. 10,000. B cannot claim set-off for any amount due to him towards salary for performing illegal activities of A. 4. It must be recoverable by the defendants or by all the defendants if more than one. For e.g. A sues B and C for Rs. 1000. B cannot set-off a debt due to him by A alone. 5. It must be recoverable from the plaintiff or all the plaintiffs if more than one. For e.g. A and B sue C for Rs. 1000. C cannot set-off a debt due to him by A alone. 6. Such sum should not exceed pecuniary limits of the jurisdiction of the court. 7. Both parties must be in same character in set-off as well as in the suits. For e.g. A dies intestate and in debt to B. In a suit for purchase money by C against B, the latter cannot claim set-off of the debt for price, for C fills two different characters, one of the vendor to B in which he sues B and the other as representative of A. [Illustration (b) to Rule 6]. Equitable Set-off [Order VIII Rule 19(3)] - Order VIII Rule 19(3) recognize equitable set-off which can be claimed by the defendants in respect of even an unascertained sum of money provided that both the cross-demands arise out of one and the same transaction [Bhupendra Narayan v. Bahadur Singh6]. For e.g. in a suit by servant against his master for salary, the latter can claim set-off for the loss sustained by him due to negligence of servant.

Consequences of failure to file written statement within the prescribed time: Rule 1 of Order 8 prescribes the time limit within which the defendant should present his written statement. Before the Amendment Act of 2002, the requirement was presentation of written statement at or before the first hearing of the suit or within such time as the court may permit. After this amendment, in order to expedite disposal of cases, 30 days time period from the date of service of summons upon the defendant has been prescribed for the filing of written statement and if the defendant fails to present the written statement within the said period, this period can be extended by the court but it shall not be later than 90 days from the date of service of summons upon the defendant and court shall record reasons for the extension of time. Rule 5(2) of Order 8 states that where the defendant has not filed his pleading, court can pronounce judgment on the basis of the facts contained in the plaint (except as against a person under disability). But even in such a case court has discretion to require such fact to be proved and this discretion of the court will be guided by the consideration whether the defendant could have or has engaged a lawyer. When court pronounces judgment under this rule, a decree shall be drawn up in accordance with the judgment which shall bear the date on which the judgment was pronounced.O 8 R5(4). As per rule 9 of Order 8, after the defendant has presented his written statement, no subsequent pleading other than by way of defence to set off or counter claim shall be presented except by the leave of the court and upon the terms fixed by the court. But the court may, in its discretion require a written statement or additional written statement from any of the parties and fix a time of not more than thirty days for presenting the same. And lastly, rule 10 of Order 8 provides for procedure when a party fails to present written statement called for by court. It says that when the written statement is required from the defendant under rule 1 or rule 9, and he fails to present the same within the time fixed or permitted by the court, the court shall pronounce judgment against him, or make such order in relation to the suit as it thinks fit and on the pronouncement of such judgment a decree shall be drawn up. Now question arises whether the defendant loses his right to file the written statement after the stipulated time period or the court has power to entertain the written statement beyond such time period. There are divergent views on this matter. According to one view, the words used in O8 R1 are precise and unambiguous and, therefore, the basic rule of interpretation must be followed, viz. where the language of rule is clear, the Court cannot abstain from giving effect to it merely because it would lead to more hardship. Therefore, howsoever, it may be harsh to the party, if the language of the amended O8 R1 is plain and simple, then effect should be given to the same and it cannot be read otherwise. Earlier the Court's power to permit filing of written statement was not hedged in by any limitation. As a result a defendant could avoid filing of the written statement on one pretext or the other postponing the trial of the suit indefinitely which was found to be objectionable. Therefore, to curtail the delay, the legislature regulated the discretion to be exercised by the Court. The discretion conferred upon the Court is not taken away but it is now regulated by prescribing the limitation upon the Court for exercising such discretion. Therefore, if O8 R1 is read in any other manner, for instance to hold the provisions directory, then the words “which shall not be later than 90 days from the date of service of summons” will be rendered nugatory and redundant. (Prahakar Madhavrao Mule v. Bhagwan Mitharam, 2004 (2) Mh.L.J.1058). The other view is that the intention of the legislature in introducing the amended provisions of O8 R1 is not to penalize the defendant who does not submit his defence within the stipulated period or to take away the discretion that was vested in the Court prior to the amendment. Procedural Rules are normally not considered mandatory in nature. Procedure is something designed to facilitate justice. The provisions of O8 R1 are therefore directory in nature. Rules 9 and 10 of Order 8 give discretion to the trial Court to allow the defendant to file written statement even after the expiry of a period of 90 days. But the provisions of O8 R1 should always be kept in mind while passing order extending time for filing written statement and ordinarily such extension shall not be granted except in exceptional and special circumstances (Chintaman Sukhdeo Kaklij and Ors. V. Shivaji Bhausaheb Gadhe & Ors., 2004 (5) BomCR 573). Similar observations have been made by the apex Court in Salem Advocate Bar Association, Tamil Nadu v. Union of India (2005(2) ACJ 492), wherein it was held that the provisions of O8 R1 CPC are directory in nature. It intends to curb the mischief of unscrupulous defendants adopting dilatory tactics, delaying the disposal of cases; causing inconvenience to the plaintiffs. The object is to expedite the hearing and not to scuttle the same. While justice delayed may amount to justice denied, justice hurried may in some cases amount to justice buried. All the rules of procedure are the handmaids of justice. Unless compelled by express and specific language of the statute, the provisions of CPC or any other procedural enactment ought not to be construed in a manner which would leave the court helpless to meet extraordinary situations in the ends of justice. Moreover, rule 10 of Order 8 is worded as, “the court shall pronounce judgment against him, or make such order in relation to the suit as it thinks fit.” It makes it clear that it is not mandatory for the court to pronounce judgment against the defendant in default. It can also make any other order in relation to the suit as it thinks fit which may also include the order to file written statement beyond the stipulated time period. In Naveed Ahmed v. Karnataka Bank Ltd. 2016 (4) AIR Kar R 189, Karnataka High Court has held that when the defendant fails to file the written statement , it may be lawful for the court to pronounce the judgment on the basis of the facts contained in the plaint. But merely because it is lawful, it does not mean that the Court should abdicate its function of finding out as to whether the plaintiff has made out a case or not. Provisions of O8 R10 of CPC are not mandatory, in the sense, giving no option to the Court except to pass a judgment in favour of the plaintiff. Court has to comprehend facts and circumstances of each case and consider plaintiff’s case set up in the plaint and see if the the case is made out in favour of the plaintiff.

*Important Applications* *1. Application for Temporary Injunction. (ORDER 39 Rules 1 & 2)* *2. Application for Rejection of plaint. (ORDER 7 Rules 11)* *3. Application for Return of plaint. (ORDER 7 Rules 10).* *4. Application for Amendment. (ORDER 6 Rules 16 & 17)* *5. Application for Appointment of Commissioner. (Section 75 & ORDER 26).* *6. Application for Appointment of Receiver. (ORDER 40)* *7. Application for Amendment of issues, or Framing Additional Issues. (ORDER 14 Rule 5).* *8. Application for production of a witness not mentioned in list of witnesses. (ORDER 16 Rule 1)* *9. Application for production of document. (ORDER 13).* *10. Application for Addition, deletion, or transposition of parties. (ORDER 1 Rule 10, sub-rule (2).* *11. Application for Stay of Suit, “Res-subjudice”. (Section 10).* *12. Application for Setting aside Exparte Proceedings and Exparte Decree. (ORDER 9 Rules 6 & 13).* *13. Application for Restoration of Suit. (ORDER 9 Rule 9).* *14. Application for Withdrawal of Suit, with or without permission to file fresh one. (ORDER 23).* *15. Application for permission to sue as a Pauper. (ORDER 33).* *16. Application for Review of Order/Judgment. (Section 114 and ORDER 47).*

EXPLAIN THE VARIOUS GROUNDS FOR EXERCISING JUDICIAL CONTROL OVER “ADMINISTRATIVE DISCRETION” IN INDIA WITH HELP OF DECIDED CASES. ADMINISTRATIVE DISCRETION: Meaning: Discretion implies power to make a choice between an alternative course of action or inaction. The term itself implies vigilance, care, caution and circumspection. Coke proclaimed Discretion as a science or understanding to discern between falsity and truth, between right and wrong, between shadows sand substance, between equity and colourable glosses and pretences, and not to do according to their wills and private affections. In short, here the decision is taken by the authority not only on the basis of the evidence but in accordance with policy or expediency and in exercise of discretionary powers conferred on that authority. In Secy. Of State for Education and Science Vs. Metropolitian Borough Council Tameside. Lord Diplock said “ the very concept of administrative discretion involves a right to choose between more than one possible cause of action on which there is room for reasonable people to hold differing opinions as to which is to be preferred. There are different types of discretionary powers conferred on the administration. They range from simple ministerial functions like maintenance of birth and death register regulation of business activity, acquiring property for the public purpose, investigations, seizure, confiscation and destruction of property, experiment or detention of a person or subjective satisfaction of the administrative authority and the like. The need for administrative discretion arises to meet variability of situations in the interests of public. But an administration unrestrained in its power to pursue its socialistic objectives by any and all means considered expedient by the officials of government is anti-thesis of law and is nothing but administrative lawlessness. Administrators who do as they like and who are not bound by considerations capable of rational formulation cannot be said to act within the framework of law. When discretionary power is conferred on an administrative authority, it must be exercised according to law. When the mode of exercising a valid power is improper or unreasonable, there is an abuse of the power. There are several forms of abuse of discretion. The excess or abuse of discretion may be inferred from the following circumstances: a. Actingwithoutjurisdiction b. Exceedingjurisdiction c. Arbitrary action. d. Irrelevantconsiderations. e. Leavingoutirrelevantconsideration f. Mixed considerations g. Mala fide h. Collateralpurpose:improperobject; i. Colourable exercise of power; j. Colourable legislation; fraud on Constitution k. Non-observance of natural justice; l. Unreasonableness.

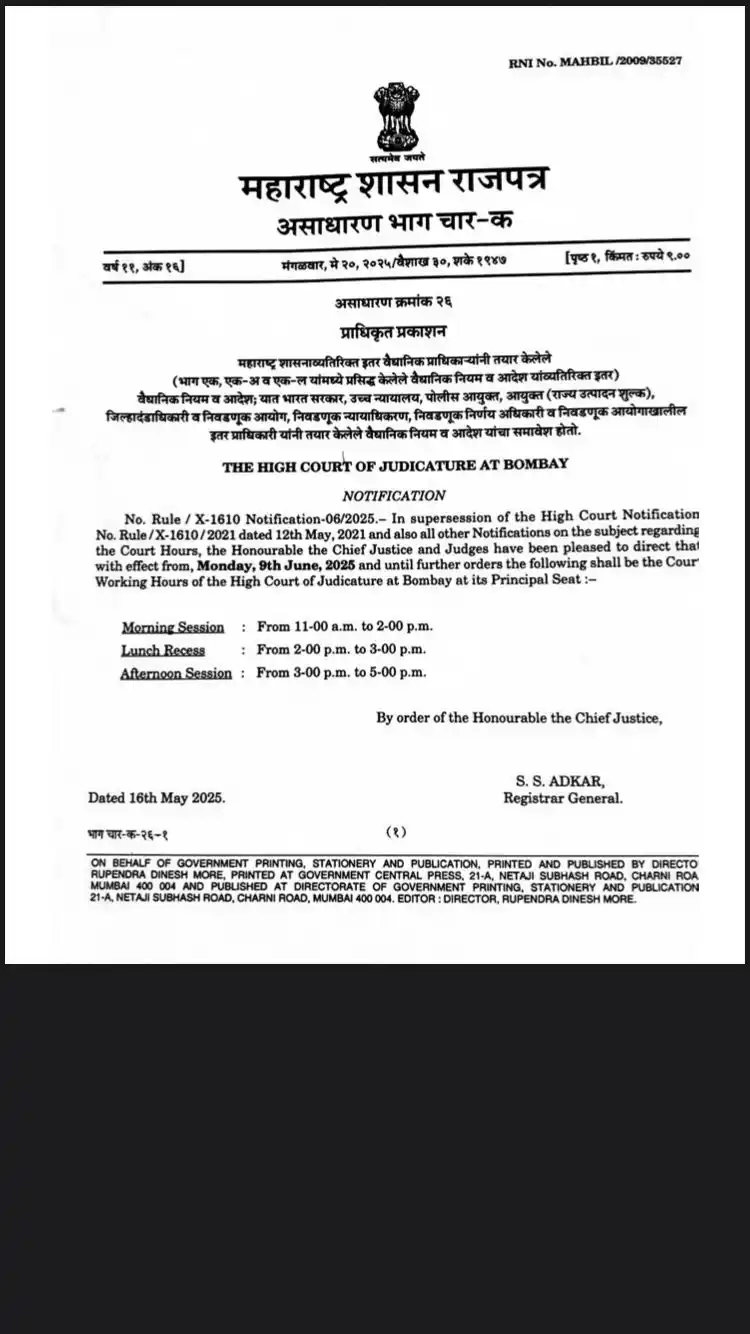

The Bombay High Court has notified a change in its sitting hours, effective 09/06/2025.